By Alexander McMillan

ABSTRACT:

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, designed by Peter Eisenman in 2005, is a deconstructivist installation located in Berlin, Germany. The memorial is designed using 2711 grey concrete stelae (thick rectangular columns) of varying heights, set out in narrow gridded rows, on an undulating paved ground plane. Eisenman conceptualised a memorial with no clear signification, a monument which does not evoke an obvious meaning. If the text of architecture is meant to be “read,” a space with no clear meaning, undoubtedly allows it to be read in multiple ways. An open text means that Eisenman’s Memorial in Berlin permits daily activities to take place in it and it’s surroundings; existing within the city itself. The non-symbolic features of the Monument allows for multiple interpretations of the way in which the space should be used and occupied. But, why is the nature of this memorial’s architectural text open-ended? Why is it structured the way it is, and how does this condition function in architectural circumstance? This essay aims to analyse Eisenman’s intellectual perception of the architectural realm and will attempt to contextualize the Memorial in Berlin as an outcome of his deconstructivist principles: the void, the absent and the present. Daniel Liberskind’s deconstructivist Jewish Museum in Berlin is used as a comparative counterpoint within the essay to express the importance of the void in order to achieve the decentering of the human subject, as it provides new forms of reference within architecture. It is highlighted that the Memorial is the last phase of Eisenman’s interrogation of architectual signification as a textual mode of operation, allowing one to understand Eisenman’s entire work, turning towards his dissertation, to best articulate what he wanted to express in relation to deconstructivism and towards the Holocaust.

Peter Eisenman has stated that the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, located in Berlin, “has no function, it has no purpose, it has no goal, it has no message, and yet three million people in one year came here.”[1] This essay examines how architectural signification acts a textual mode of operation, and how this relates to the open ended nature of Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial. The essay begins by examining Eisenman’s deconstructivist architectural perception: allowing architectural form to become an autonomous entity. It goes on to contextualise the Memorial in Berlin as an outcome of his deconstructivist principles: the void, the absent and the present. Daniel Liberskind’s deconstructivist Jewish Museum in Berlin is used as a comparative counterpoint within the essay to express the importance of the void in order to achieve the decentring of the human subject, as it provides new forms of reference within architecture. The essay then examines the Memorial itself, and its lack of architectural signification which allows for open-ended interpretations and “readings” of the space. The essay concludes by affirming that a monument that does not dictate any particular meaning or experience, raising new notions of our relationship to the Holocaust, and the intended purpose and use of memorial architecture.

Eisenman’s Deconstructivist architectural perception.

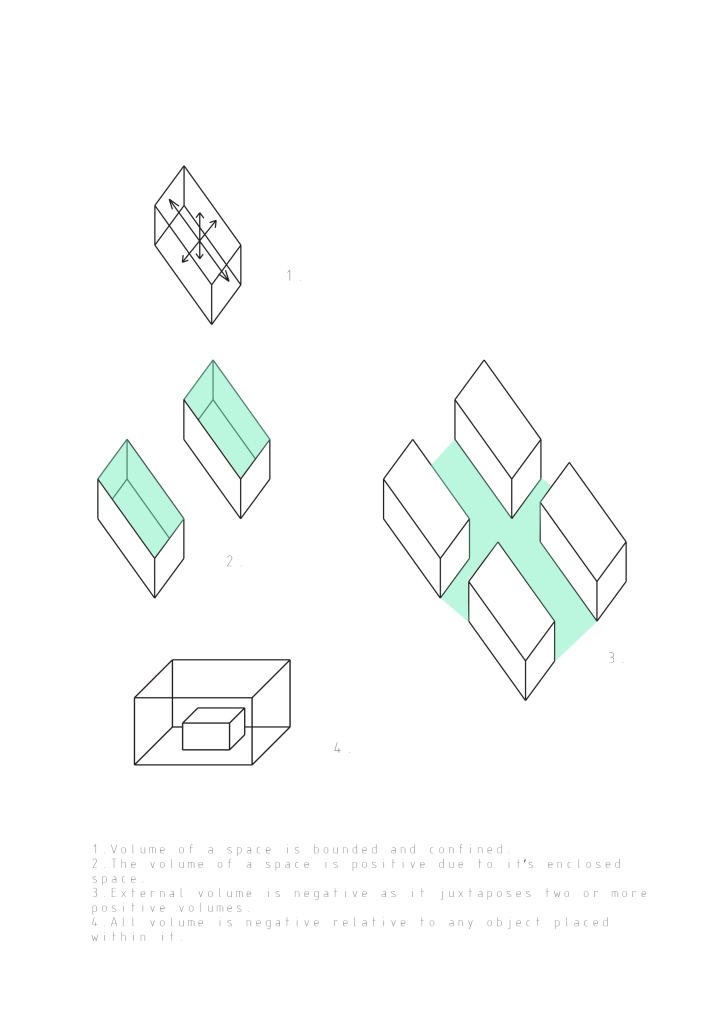

Eisenman’s dissertation, which expressed his structuralist mode of thinking, attempted to define the language which reflects architectural form. He claims that it is not historical but rather based on the dialectal structures that allow form to become autonomous, without relating to its original context. With this new perception of architecture, Neuman argues that Eisenman “proposed a new model for architectural analysis and thinking. Form is in the basis of architecture.”[2] Hays affirms this idea arguing, “Architectural form is understood to be produced in a particular time and place, of course, but the origin of the object is not allowed to constrain its meaning.”[3]

Not only did his dissertation argument reflect the ideas prevailing in contemporary architectural discourse, but his thesis further proposed a new way of thinking about architecture as a whole. Using the structuralist way of thinking, taken from the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure, Eisenman argued to produce architectural signification as a textual expression, expressing the separation between the signed and the signifier. Drawing upon De Saussure’s examination of a synchronic language to construct meaning, Eisenman claims that meaning in architecture is due to the interrelationship between the various parts that produce the syntactical structure of architectural language. In order to achieve this, Eisenman broke down the utilitarian function and symbolic function of architecture, affirming:

“For the past fifty years, architects have understood design as a product of some oversimplified form-follows-function formula. This situation even persisted in the years following World War II, when one might have expected it would be radically altered. And as late as the end of the 1960s, it is still thought that the polemics and theories of the early Modern Movement could sustain architecture.”[4]

Eisenman’s problem with Louis Sullivan’s ‘form follows function’ idiom was not to disrepute functionality in architecture, but instead was an attack on the two mains streams that focused on the idea: the neo-technologists and those who viewed modernism as a rejection of humanist principles. Referring to the latter, Eisenman believed that by focusing on architectural functionality, the human subject is still placed as the essential part of the architectural realm. MacArthur Affirms this idea arguing that deconstructivist architecture is a paradoxical account of human presence in architectural theory, stating that:

“According to Eisenman, his work then leaves “deconstructed” the traditional architectural dichotomies of structure and decoration, abstraction and figuration, figure and ground, form and function, those paired terms which swung about the centre of the question of the possibility of our presence before them.”[5]

This idea was fundamental to one of Modernism’s leading architects, Le Corbusier, through his exploration of the human body as central to architectural creation.[6] In Post Functionalism, Eisenman draws parallels between the humanist and modernist movement; however this only serves to discredit the humanist-functionalist architecture that was built during the years following post-war period. [7]

Eisenman was heavily critical of the neo-technologists and their favourable view of technology throughout the 1950s and 60s. Projects like Archigram, which relied heavily on advanced technology and engineered systems, pushed the idea of form-follows-function to its extremes. Taking into consideration Corbusier’s principle of architecture being “a machine for living” literally, architecture became and was meant to function as a machine. Neuman states that for Eisenman, “this symbolized the complete dominance of the utilitarian function over architecture, posing a danger that architecture would be perceived and produced only as an outcome of functionalism.”[8] Eisenman aimed to dissociate form, function and meaning and allow them to exist on their own, permitting meaning to prevail once form is conceptualised, but not as a consequence of function.

The dissolution of architectural function, in the eye of Eisenman, saw a concentration on form reflecting other modernist avant-garde architects whom sought to create architecture for the sake of architecture. Eisenman declared, in relation to the programming and functionality in architecture:

“I do not think function has to do anything with architecture at all. Does it matter that Santo Spirito and San Lorenzo in Florence had the same programme, same size Church, completely different architecturally. Why was it different architecturally? Because, Brunelleschi was trying to do something with the architecture. He did not give a damn about the function. And it functioned- as long as it functioned, it functioned.”[9]

Eisenman’s formal articulation that the form of architecture is an autonomous entity that must relate to its own properties, led to the idea that the form should be a separate entity that is not necessarily related to the reality it is meant to address.

The Void, the Absence, the Presence.

Eisenman’s interrogation of architectural language was further developed throughout the 1980s with the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, and his exploration of spatiality stemming from classical philosophy. Eisenman worked alongside Derrida in their proposal for competition designing Parc de La Villete, located in the periphery of Paris, examining Plato’s principal of the chora. Plato defined the chora as a space which exists between the logical and the practical. The logical refers to reason from the world of ideas, while the practical stems from the material world. Thus, this principle lies between reason and matter, and is neither logical nor practical, while at the same time being both; and can only be expressed in architecture as a means of creating place.[10]

In Derrida and Eisenman’s book titled Chora L Work, Derrida states, “Chora is something that cannot be represented…. Except negatively,” arguing further that it is a space which cannot be represented, challenging the built form of architecture.[11] In this instance, he is challenging Plato’s concept with a discourse on structure without origin, essence and hierarchy. For Derrida the concept of the chora is the non-material as well as the non-ideal; it sets a standard for creating space and designing a spatial condition that is not defined by orientation or direction.

From this dissertation, Eisenman related to the concept of making the absent present, and the present absent, and associated them to spatial existence. If the chora exists between the ideal and the material, then in architectural terms, the concept must deal with architectural presence and absence. For Eisenman, materiality in architecture is always present, and the ideal absent, with the interchange between the two leading to a space that is not necessarily logical or practical. Eisenman refers to this concept in Chora L Work arguing:

“In the work that we have been doing, we distinguish between the presence of absence and the absence of presence. What we are trying to do is to create an architectural text, which while centring, at the space time speak of another, a decentring.” [12]

In this statement, Eisenman refers to his deconstructivist discourse, as the role of architecture being a text, existing beyond its material presence.

The concept of decentring the human subject is present in the work of the deconstructivist architect Daniel Libeskind, who achieves this condition through the concept of the void. In his design of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Libeskind refers to absence and presence as an architecture means of creating non-representations; with the concept of the void alluding to absence and presence. In the Museum, the void is represented through the intersection of the two building parts: the straight and the zigzag. At this junction, an implicit absence, a void, is left.

While both Libeskind and Eisenman were a part of the deconstructivist architectural movement throughout the 1980s and while they both refer to ideas in the deconstructivist discourse, their interrogation and application of presence and absence is somewhat different. Libeskind employed these concepts through representation that alludes to the abstract, the inconceivable and the transcendent. Undeniably, the absent or the voided leaves traces yet in the work of Libeskind, these traces are only references alluding to previous presence which do not materialize in the present. Eisenman too refers to the traces which absence leaves, however unlike Libeskind, the application of this concept is not through symbolic refers or any other form of representation, nor does it try to establish that they were once present. Instead for Eisenman presence, absence and void challenges the nature of architectural signification. Eisenman’s partner, Cynthia Davidson describes,

“Whether moving backward or forward in time, the void, the presence and absence appears repeatedly in Eisenman’s work. In a continuing confrontation with meaning and signification, Eisenman relies again and again on process as a way to “free architecture of its own traditional language and concerns,” that is, from presence as a manifestation of truth.” [13]

Thus, for Eisenman absence functions to create conditions in which architectural presence does not allude to an absolute reference. Instead it relies on multiple references deconstructing the definitive language of architectural language. It is a condition which allows architecture to become open-ended, with no specific signification.

Libeskind and Eisenman differ on their perception of the void, the absence and the presence in architecture. Libeskind uses presence and absence to reference the loss and destruction of the Holocaust; the void. Neuman argues that that the voided space is immeasurable and cannot be represented symbolically, raising the paradox,

“How can a void exist in a practice such as architecture that celebrates existence? How can a void exist in a practice based on material and spatial existence? Libeskind leaves these questions open, only allocating spaces that generate this paradox.”[14]

In Eisenman’s work the issue of absence, presence and void are way of generating new meaning in architecture. The Aronoff Centre for Design and Art in Cincinnati and the Nunotani Corporation Headquarters in Tokyo are two Eisenman projects that include active voids. The Design of each project stems from intensive research into spatial organisation through the geometric analysis of the building’s site. The design of each building includes voided parts in the allocation of space, with no specific signification. Davidson argues,

“A deep analysis of the site projected onto the strictly formal manipulation of geometric, often L-shaped form, produces voids that become more purposeful than in House II. These voids are active spaces that change how the building is viewed and occupied. In the Nunotani building, the void is an expanding vertical volume of light that breaks up large office floor plates; at the Aronoff, it is still a tall central space around and through which students and faculty circulate, with ever changing views of both the building and its inhabitants.”[15]

These two projects emphasis that Eisenman does not use the void to allude to an absence that used to be present. Instead, they refer to what will be present in the future. Thus, the voids allow the buildings to be read, understanding how they should be occupied in relation to programmatic and spatial organisations.

Eisenman uses architectural language a means of interrogating architecture signification through presence, absence and the void. The use of these concepts does not suggest a fixed meaning, instead it operates undecided, with no clear signification, offering a framework for content in the future. For Eisenman, this allows the absent to allude to the non-existent, to become present, allowing for the emergence of new concept making in architecture.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.

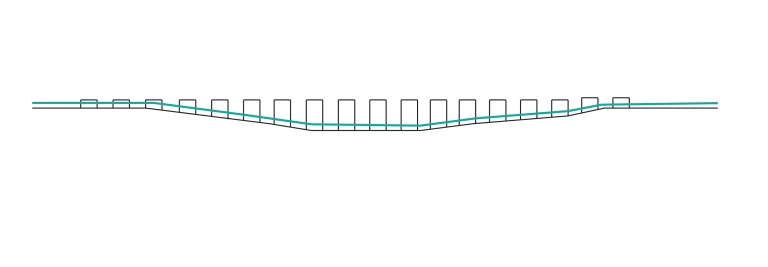

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, is an installation designed by Peter Eisenman, as part of a competition in 1997 to design a memorial in the German capital, honouring the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. The memorial is comprised of 2711 blank, dark grey concrete stelae (thick rectangular columns, used in ancient times as commemorative markers). The stelae are 2.38 metres long and 0.95 metres wide, and vary from 0.2 to 4.8 metres high.[16]

Eisenman has stated that the Memorial carries no symbolic significance and that the use of stelae as a representation of tombstones or graves, was not intended; In fact he has never revealed his intentions behind designing the field of slabs. Neuman argues that, “this might have been deliberate, out of a desire to keep the significance of the Memorial open to endless interpretations”[17], helping to preserve the Memorial as an open text awaiting individual interpretation.

The arrangement of the stelae in a grid-like pattern has been widely believed to resemble the organization of a city. Referring to the similar configuration of an American city, this layout stemmed from a desire to create a democratic arrangement.[18] Although artificial and nonorganic, “The urban grid was perceived as a means of imposing human organization on nature. As a system that has no beginning and no end, the grid was also referred to as enabling endless growth”.[19] The notion that each plot in the democratic grid arrangement was treated equally, is associated with the equality of death and that all people should be remembered equally. Furthermore, the grid’s open-ended configuration creates a conceptual condition in which the Memorial, like a city, is able to grow. The Memorial has no clear entry or exit, and is able to be accessed from all of its peripheral boundaries. At the installation’s edge, the stelae fade into the ground leaving the impression that they could continue endlessly.

The idea of the grid is not just referenced in Eisenman’s architectural theory, but in the context of the 20th Century artist Rosalind Krauss and her study of abstraction. Krauss’ discussion of the grid in relation to the avant-gardes of the 20th Century is directly linked to Eisenman’s interests and architectural concerns; both dealing with the issues of autonomy and self-referential expression. Krauss relates these ideas to the early twentieth century artistic expression:

“In the spatial sense, the grid states the autonomy of the realm of art. Flattened, geometricized, ordered, it is antinatural, antimimetic, antireal… the grid is the means of crowding out the dimensions of the real and replacing them with the lateral result not of imitation, but of aesthetic decree… to be in a world apart and, with respect to natural objects, to be both prior and final.”[20]

In many ways, Eisenman’s Memorial responds similarly, existing outside of the Holocaust or other architectural narratives, attempting to be antimimetic and particular to itself. The function of the grid can be associated with Eisenman’s entire work, with the Memorial being the last phase of this interrogation, and his occupation with architectural autonomy.

Diagram Two demonstrates the undulating ground emphasizing the architectural autonomy of the Memorial. Moving within the space forces visitors to climb up and down, whilst wandering through the narrow, maze like configuration of the stelae. Stephens argues that the feeling of displacement “creates an immensely powerful kinaesthetic, tactile, and visual experience.”[21] The narrow pathways, looming stelae, and the ground sinking to 2.5 metres at its lowest point, causes the visitor to feel lost, or at least removed and isolated from the rest of the world. Architects like Claude Parent and Paul Virilio dealt with movement on oblique surfaces throughout the 1960s, addressing the idea that the eye should not be the primary sense that dictates and directs human movement within an architectural space. [22]

The memorials open ended nature allows everyday activities to take place within and around it, challenging what is considered appropriate for a memorial site. Neuman argues:

“For Eisenman, the Memorial as open text had to allow the emergence of non-dictated behaviours; as an open condition it must allow the “reading” of the architectural text in multiple ways. These “readings” are conveyed through the appropriation of the site in any given way.”[23]

He goes on to argue that these interpretations dictate the way which the Memorial should be appropriated, defining how architecture must be used.

In conclusion, Eisenman’s memorial constructs a signification system of a meaning which is yet to come. The non-representational nature of the memorial, which has a notable absence of symbolism related to the Holocaust, allows the installation to have multiple meanings whilst still retaining an idea that is related to the event that it memorialises. This means however that someone visiting the site would not necessarily recognise it as a memorial, nor its role as a commemoration to those exterminated by the Nazis. Yet, the memorial acts an architectural text which serves its function of relating to the topic it addresses, making it plausible to accept it as a commemoration of the Holocaust. The memorials open ended nature allows the insertion of new activities that carry new meanings into the Memorial’s context and the commemoration of the Holocaust; representing the Holocaust as an event that does not have a tight signification or closed but instead an event that can absorb daily activities without losing its primary role. Through the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Eisenman has created a unique opportunity for Holocaust commemoration, a monument that does not dictate any particular meaning or experience, but rather raises new notion of our relationship to the Holocaust.

Bibliography:

Davidson, Cynthia, Tracing Eisenman: Complete Works, (New York, 2006).

Derrida, Jacques, “Chora” in Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman, Chora L Works.

Eisenman, Peter, “Interview,” in Yasha Grobman and Eran Neuman, Performalism: Form and Performance in Digital Architecture, DVD, Tel Aviv: 2008.

Eisenman, Peter, “Post Functionalism.” In Oppositions (New York, 1976).

Hays, Michael, “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Form.” In Perspecta (1984).

Krauss, Rosalind, “Grids” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, (Cambridge, 1985).

Leslie, Martin, “The Grid as Generator,” in Architectural Research Quarterly, (2000).

Le Corbusier, The Modular: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale, Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, (Basel, 2000).

Macarthur, John, “Experiencing Absence: Eisenman and Derrida, Benjamin and Schwitters,” in Knowledge and or Experience: the theory of Space in Art and Architecture, (Brisbane, 1993).

Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014).

Parent, Claude et al, The Function of the Oblique, (London, 1996).

Plato, The Timaeus of Plato, (New York, 1973).

Stephens, Suzanne, “Peter Eisenman’s vision for Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,” in Architectural Record, 2005.

[1] Peter Eisenman, “Interview,” in Yasha Grobman and Eran Neuman, Performalism: Form and Performance in Digital Architecture, DVD, Tel Aviv: 2008.

[2] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 153.

[3] Hays, Michael, “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Form.” In Perspecta (1984) p.16

[4] Eisenman, Peter, “Post Functionalism.” In Oppositions (New York, 1976), pp.30-44

[5] Macarthur, John, “Experiencing Absence: Eisenman and Derrida, Benjamin and Schwitters,” in Knowledge and or Experience: the theory of Space in Art and Architecture, (Brisbane, 1993) p.103.

[6] Le Corbusier, The Modular: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale, Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, (Basel, 2000).

[7] Eisenman, Peter, “Post Functionalism.” In Oppositions (New York, 1976), pp.30-44

[8] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 155.

[9] Peter Eisenman, “Interview,” in Yasha Grobman and Eran Neuman, Performalism: Form and Performance in Digital Architecture, DVD, Tel Aviv: 2008.

[10] Plato, The Timaeus of Plato, (New York, 1973).

[11] Derrida, Jacques, “Chora” in Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman, Chora L Works, p.10.

[12] Eisenman, Peter, Chora L Work, p.9.

[13] Davidson, Cynthia, Tracing Eisenman: Complete Works, (New York, 2006), p.29

[14] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 161.

[15] Davidson, Cynthia, Tracing Eisenman: Complete Works, (New York, 2006), p.30

[16] Stephens, Suzanne, “Peter Eisenman’s vision for Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,” in Architectural Record, 2005, p.120-127

[17] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 170.

[18] Leslie, Martin, “The Grid as Generator,” in Architectural Research Quarterly, (2000), pp.309-22

[19] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 170.

[20] Krauss, Rosalind, “Grids” in The Origininality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, (Cambridge, 1985), p.9

[21] Stephens, Suzanne, “Peter Eisenman’s vision for Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,” in Architectural Record, 2005, p.120-127

[22] Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, The Function of the Oblique, (London, 1996).

[23] Neuman, Eran, “Diagramming Memory: Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin” in Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust, (England: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014), 173.